In a New York City Minute: Bird-Friendly Retrofit at the World Trade Center

category: VOLUNTEER!CONSERVATIONURBAN BIRD CALL

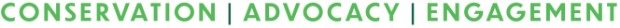

The glass railing at the World Trade Center's Liberty Park, treated with Feather Friendly to prevent collisions. Photo: Melissa Breyer

IN A NEW YORK CITY MINUTE: BIRD-FRIENDLY RETROFIT AT THE WORLD TRADE CENTER

This article appears in the fall 2021 issue of The Urban Audubon.

By Suzanne Charlé

If you visit Liberty Park, overlooking the 9/11 Memorial at the southern tip of Manhattan, look closely: The raised park’s glass railing—now sporting thousands of small gray dots—is the most recent step in making New York City safer for birds. The change is the result of a cooperative effort on the part of volunteers, bird conservation organizations, architects, and the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, which oversees the park.

It all started in the fall of 2020, when Project Safe Flight volunteer Melissa Breyer was monitoring the World Trade Center campus for bird strikes against building facades. Entering Liberty Park, she was stunned. “Four birds were dead. ‘What?!?’,” she remembers thinking. “It’s unusual to see four in one spot, even near a bad building.” Then she saw two birds crash into the park’s glass railing and bounce off.

Breyer lives in Brooklyn and couldn’t get to the site often, so she told her friend and fellow Project Safe Flight volunteer Calista McRae, who lived closer to the World Trade Center.

“It was nasty,” McRae recalls. Birds were colliding with the park’s clear glass railing, about 20 feet above the 9/11 Memorial. “The birds in Liberty Park could see the oak trees around the memorial and flew right into the glass.” The volunteers kept close watch, saving birds when they could. In all, more than 1,200 stunned or dead birds were found in the World Trade Center area that fall.

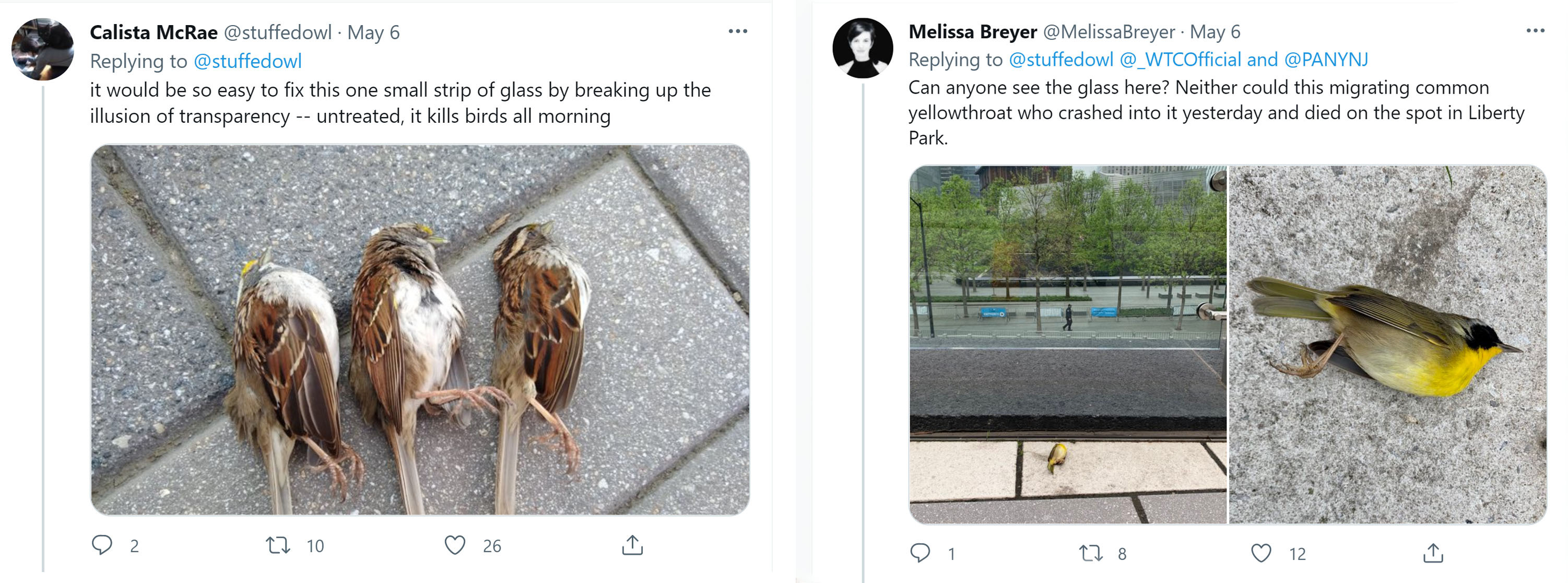

In early May during spring migration, McRae was back in Liberty Park and found three dead White-throated Sparrows. She looked over the glass railing: a Common Yellowthroat was stunned but still alive in the parking area below. “It was high security and closed to the public,” she recalls. Before she could ask the guards to try to rescue it, a truck ran it over.

McRae and Breyer felt drastic action was necessary to let people know about this ongoing danger to birds. “I tweeted several photos: @_WTCOfficial, @PANYNJ,” says McRae. Breyer tweeted as well. The tweets were noticed by others, and Beverly Mastropolo, a wildlife rehabilitator, contacted local journalists.

Media hopped on the story: On May 12, the New York Post ran an article. The next day CBS2 interviewed the Project Safe Flight volunteers and documented how glass railings and windows could be “deathtraps.” After the first news story, Breyer says, two guards walked up to her and pointed up at the railing, shaking their heads. “Clearly things were going to change.”

The Port Authority said it was “looking into the matter.” And it was, reaching out to NYC Bird Alliance and the American Bird Conservancy (ABC) for input. Christine Sheppard, ABC’s bird collisions campaign director, was ready with advice about possible retrofits the Port Authority might make. For over 10 years, ABC has explored what works and what doesn’t, and like NYC Bird Alliance and the American Institute of Architects, it played a major part in the development and passage of New York City’s Local Law 15 of 2020, which requires all new construction and significantly altered buildings to use bird-friendly materials.

The Port Authority architect called Canada’s Feather Friendly Technologies, a world leader in applications on glass that allow birds to “see” windows and avoid deadly collisions—estimated to cause about one billion bird deaths each year in the U.S. Paul Groleau, the company’s vice president, recalls that the Liberty Park architect described the problem and asked “‘Can you help us out? Can you send pictures?’ They wanted to get it done ASAP.” Feather Friendly overnighted several samples for approval of two patterns, in gray and black, enough to cover four panes of the park’s glass railing.

“The response was immediate,” says Groleau. As soon as the Port Authority got the samples, Feather Friendly’s partners installed them. Sheppard got a call from the Port Authority “asking if I might come down the next day—they were going to do it and were on the move. It was so encouraging. And it looked fine!” (The current, eighth generation of Feather Friendly is a pattern made up of two-by-two-inch squares, “the recommended spacing pattern to mitigate collisions for all bird species, including hummingbirds,” says Groleau. The product, tested and approved by ABC, was recently installed at Brooklyn’s Marine Park’s Salt Marsh Nature Center and at the Jamaica Bay Wildlife Refuge Visitor Center in Queens.)

By June 2, the Port Authority was installing the bird-friendly dot pattern on the park’s entire railing. “We’re thrilled,” says Kathryn Heintz, NYC Bird Alliance’s executive director. “The Port Authority responded with such speed.” The action impressed others, too: Groleau says that there’s been a recent increase in inquiries about retrofit materials from managers of commercial and residential buildings in New York City, as well as from individuals.

Sheppard of ABC says New York City’s new law requiring bird-friendly materials for all new construction and major alterations is “the biggest deal ever.” Now, says Kaitlyn Parkins, associate director of conservation and science for NYC Bird Alliance, “we need to convince owners of all existing buildings to put mitigation in place.” NYC Bird Alliance hopes to marshal enthusiasm from the many who have discovered birdwatching during the pandemic and may not know of this major opportunity to make New York City safer for migrating birds.

Read more about NYC Bird Alliance's Project Safe Flight.