Project Safe Flight

Yellow Warblers migrate through New York City, stopping in our parks to feed and rest. This beautiful species also nests in all five boroughs. Photo: Pat Schleiffer

Helping Birds Migrate Safely Through New York City

Every spring and fall, millions of birds—from tiny songbirds to large raptors—travel through New York City along the "Atlantic Flyway" from winter grounds as far as South America to breeding grounds as far north as the Arctic. On these ancient annual journeys, they face modern, deadly threats: glass windows and artificial nighttime lighting.

NYC Bird Alliance research shows that between 90,000 and 230,000 birds are killed in the city each year in these tragic collisions, a death toll worsened by lights that confuse migrating birds.

The White-throated Sparrow, known for its sweet, plaintive song, spends the winter in New York City. It is the most frequently found collision victim here since 1997, according to Project Safe Flight data. Photo: John Pizniur/Great Backyard Bird Count

The shy and well-camouflaged American Woodcock both migrates through and nests in New York City. Many woodcocks become bewildered as they attempt to navigate the City's terrain of glass and cement. This bird was taken to Manhattan's Wild Bird Fund to be rehabilitated. Photo: MaryJane Boland

The Common Yellowthroat, indeed a common migrant and breeding bird in New York City's wilder spots, is the most frequently found collision victim here, among the warbler species. Photo: Laura Meyers

The Key Contributors to Bird Collisions

Glass

Birds don't perceive clear or reflective glass as a solid barrier. Instead, they see reflections of the sky and surrounding habitat, or they see a clear path through a building to what looks like more habitat on the other side. This optical illusion leads them to fly directly into windows. Common scenarios include:

- Reflected vegetation or sky: The glass mirrors trees, bushes, or the open sky, making birds believe it's a safe place to fly.

- Vegetation or sky behind glass: Birds might attempt to fly towards plants or sky visible through a window.

Research from NYC Bird Alliance shows that across the U.S., more than a billion birds are killed annually in collisions with windows, the second leading cause of death for birds in the country behind free-roaming domestic cats.

Artificial Light

"}" data-trix-content-type="undefined" class="attachment attachment--content">

"}" data-trix-content-type="undefined" class="attachment attachment--content">A contributor to the problem of glass is artificial nighttime lighting. Many birds, including most songbirds, migrate at night, and artificial light has been shown to attract and disorient them. Artificial light at night affects birds in the following ways:

- Attraction: Point sources of light like brightly lit skyscrapers and upward-facing beams attract birds, drawing them into urban airspace that they otherwise might avoid. Once in the City, they face a heightened risk of colliding with built structures.

- Disorientation: Once drawn in by the light, birds can get confused by the glow, fluttering erratically and leading to injury, exhaustion, or settling in unsafe areas.

Weather Conditions

"}" data-trix-content-type="undefined" class="attachment attachment--content">

"}" data-trix-content-type="undefined" class="attachment attachment--content">Weather can play a major factor in collisions. When conditions are poor, birds are more vulnerable to colliding with buildings. Weather conditions impacting collisions include:

- Low visibility conditions like fog and low clouds force birds to fly at lower altitudes, where they are more likely to encounter structures.

- Unfavorable winds (like strong headwinds) can also cause birds to fly at lower altitudes and may push birds off course and into the city.

- Reduced visibility makes it harder for birds to safely navigate their surroundings.

Building Height & Design

While skyscrapers are a big concern, it's a common misconception that only tall buildings pose a threat:

- More than half of bird-building collisions occur with buildings shorter than four stories.

- Specific architectural features like glass railings and awnings can be particularly hazardous, even on lower-rise structures.

Seeking Solutions: Project Safe Flight

Project Safe Flight began in 1997 when founder Rebekah Creshkoff and a small group of volunteers started monitoring buildings in downtown Manhattan. They quickly discovered a problem far greater than they imagined, and the project was born. Now over two decades old, it has grown to include several complementary components aimed to reduce bird deaths from window collisions in New York City:

profiles2

A stunned male Chestnut-sided Warbler is gently collected by a Project Safe Flight collisions monitor, before being taken to a rehabilitator. Photo: Sophie Butcher

Collision Monitoring

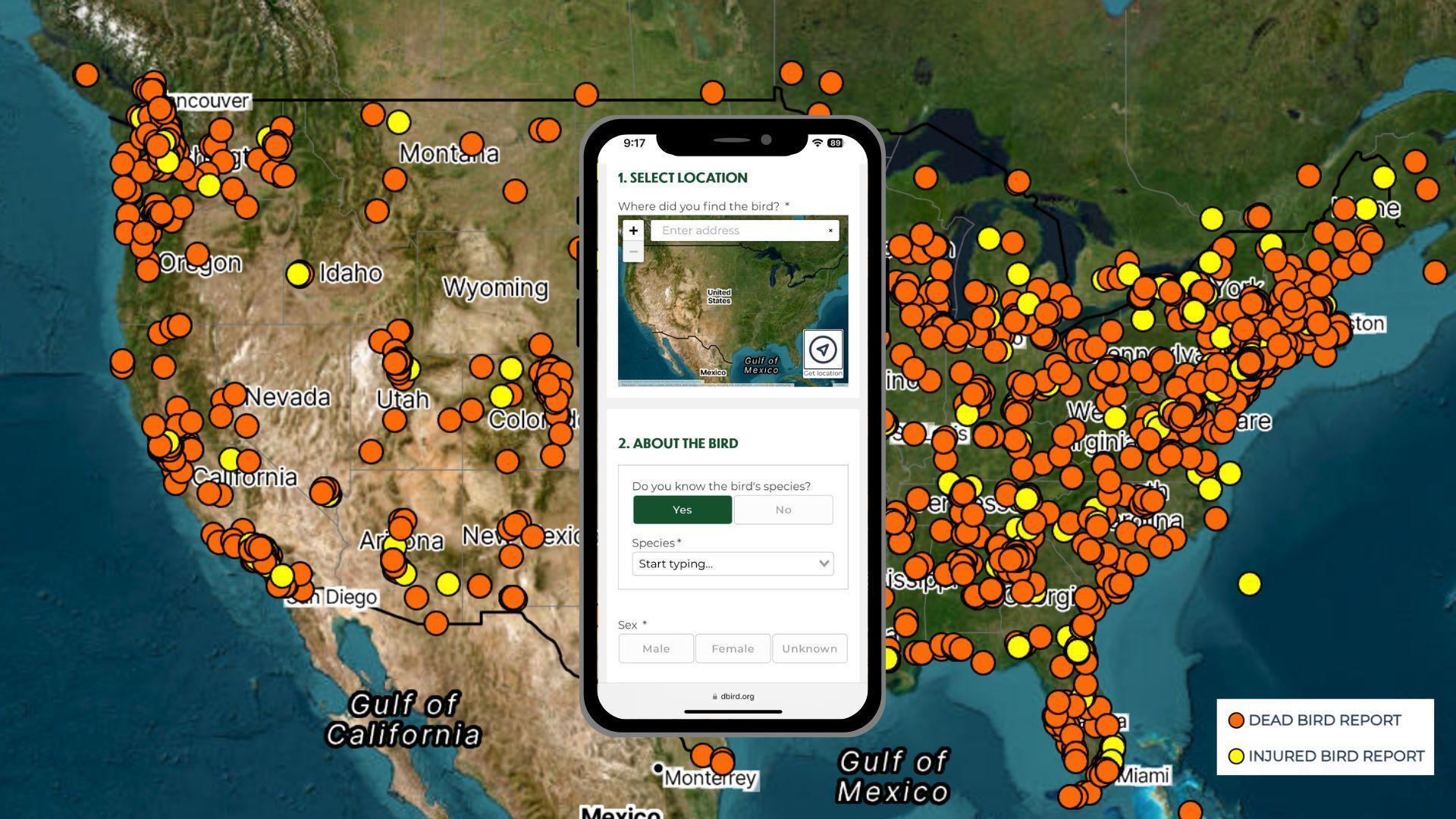

Dedicated Project Safe Flight volunteers walk regular routes during spring and fall migration to find dead and injured birds, contributing to our long-term data set in conjunction with our online dBird data-collecting tool. Our data helps to pinpoint deadly buildings in the City, and provides evidence we can use as we seek change—whether realistic solutions at specific buildings, or larger policy wins.

The fritted design of bird-friendly glass at the Jacob K. Javits Convention Center allows birds to see the building's glass and avoid collisions; since a renovation to the building, bird collisions have been reduced by as much as 90 percent. Photo: Stephanie Kale

Bird-Friendly Building Design

We fight to enact city and state legislation that mandates bird-friendly building practices. A major victory was the December 2019 passage of Int. 1482/Local Law 15 by the New York City Council. This milestone legislation requires that all new construction and significantly altered buildings use bird-friendly materials. We also educate and work with policy-makers, developers, architects, and building owners to reduce the hazards of glass and lights through the use of bird-friendly design principles.

The New York City Skyline at night. Photo: Adriano BIDOLI/CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Artificial Light

We work with research partners to better understand the impact of artificial night-time lighting on migrating birds, and its relationship to bird deaths from collisions with building glass. Though most collisions occur during the day, the amount of light emitted by a building is a strong predictor of the number of collisions it will cause. Following the recent passage of bird-friendly design legislation, NYC Bird Alliance has been advocating for legislation requiring a reduction in artificial nighttime lighting during spring and fall migration.

How YOU Can Help Reduce Collisions

Project Safe Flight is more than a research program—it's a mission to make New York City a safer place for birds. Here’s how you can join the thousands of volunteers, advocates, and compassionate New Yorkers who are actively making a difference in reducing collisions:

.jpeg)

Showcase your art on your windows and prevent collisions at the same time!

Make Your Windows Visible

You can make your windows safe for birds! A crucial guideline is the 2x2 Rule: visual markers added to glass must be spaced no more than two inches apart horizontally and vertically. Learn ways you can easily make your windows visible to birds, with solutions as simple as adding stickers!

.png)

Feather Friendly® film on the northeast corner windows at 1 Hotel Brooklyn Bridge, retrofitted in 2022. Photo: NYC Bird Alliance

Make your building bird-safe

Building managers and owners play a critical role in bird conservation. By implementing bird-friendly design, you can protect migrating birds while enhancing your building's reputation for environmental stewardship. Learn about effective solutions.

Simply turning off your unnecessary lights at night can help save birds lives.

Reduce Your Night-time Lighting

By simply turning off unnecessary lights, you can save countless birds during their journey. We ask everyone to turn off unnecessary indoor and outdoor lights between 11pm and 6am during the peak migration periods (Apr 1 through May 31 in spring, and Aug 15 through Nov 15 in fall).

dbird.org is used by conservation organizations across the country to help research bird mortality.

Report a Collision

Your data is vital to our research. If you find a dead or injured bird, please report it to our crowd-sourced database at dBird.org. This helps us identify collision hotspots and focus our conservation efforts.

And if you find an injured bird, please visit our Found an Injured Bird page for instructions on how to safely assist it and contact information for wildlife rehabilitators like Wild Bird Fund.

And if you find an injured bird, please visit our Found an Injured Bird page for instructions on how to safely assist it and contact information for wildlife rehabilitators like Wild Bird Fund.

Lights Out Rally at City Hall. Photo: NYC Bird Alliance

Advocate and Get Involved

Making New York City safer for birds requires a collective effort.

Support Legislation: NYC's Local Law 15 of 2020 requires bird-friendly materials on all new construction, but more bird-friendly policies are needed. Learn how you can help advocate for bird-friendly legislation.

Volunteer: Join our Project Safe Flight team and help us monitor collision hotspots during fall and spring migration.

Spread the Word: Tell your friends, family, and building managers how they can help.

Support Legislation: NYC's Local Law 15 of 2020 requires bird-friendly materials on all new construction, but more bird-friendly policies are needed. Learn how you can help advocate for bird-friendly legislation.

Volunteer: Join our Project Safe Flight team and help us monitor collision hotspots during fall and spring migration.

Spread the Word: Tell your friends, family, and building managers how they can help.

THANK YOU TO OUR SUPPORTERS

NYC Bird Alliance's Project Safe Flight program to reduce bird collisions is made possible by the leadership support of the Leon Levy Foundation since 2008 and grants from The New York Community Trust, Disney Conservation Fund, the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, and the Ittleson Foundation. Critical support is also provided by the generous contributions of our members and donors.

Project Safe Flight Resources and References

Bird-Friendly Building Design: Based on NYC Bird Alliance's Bird-Safe Building Guidelines, this 2019 update by the American Bird Conservancy in partnership with NYC Bird Alliance is the most authoritative resource on this issue.

Bird Collision Prevention Alliance

Bird Collisions with Windows: An Annotated Bibliography by Chad L. Seewagen and Christine Shepphard

Bird Conservation Network

Bird Collision Prevention Alliance

Bird Collisions with Windows: An Annotated Bibliography by Chad L. Seewagen and Christine Shepphard

Bird Conservation Network

FLAP Canada

LEED Pilot Credit in Reducing Bird Collisions: NYC Bird Alliance, Bird-Safe Glass Foundation, and the American Bird Conservancy successfully worked with the U.S. Green Building Council to create this pilot credit for sustainable buildings.

LEED Pilot Credit in Reducing Bird Collisions: NYC Bird Alliance, Bird-Safe Glass Foundation, and the American Bird Conservancy successfully worked with the U.S. Green Building Council to create this pilot credit for sustainable buildings.

Published Research

Chen, Katherine, Sara M. Kross, Kaitlyn Parkins, Chad Seewagen, Andrew Farnsworth, and Benjamin M. Van Doren. “Heavy Migration Traffic and Bad Weather Are a Dangerous Combination: Bird Collisions in New York City.” Journal of Applied Ecology 61, no. 4 (February 18, 2024): 784–96.

Kornreich, Ar, Dustin Partridge, Mason Youngblood, and Kaitlyn Parkins. “Rehabilitation Outcomes of Bird-Building Collision Victims in the Northeastern United States.” PLOS ONE 19, no. 8 (August 7, 2024).

Loss, S. R., Will, T., & Marra, P. P. 2015. Direct mortality of birds from anthropogenic causes. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 46:99-120.

Kornreich, Ar, Dustin Partridge, Mason Youngblood, and Kaitlyn Parkins. “Rehabilitation Outcomes of Bird-Building Collision Victims in the Northeastern United States.” PLOS ONE 19, no. 8 (August 7, 2024).

Loss, S. R., Will, T., & Marra, P. P. 2015. Direct mortality of birds from anthropogenic causes. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 46:99-120.

Additional Published Research

Cabrera-Cruz, S. A., Smolinsky, J. A., & Buler, J. J. 2018. Light pollution is greatest within migration passage areas for nocturnally-migrating birds around the world. Scientific Reports, 8:3261.

Gelb, Y., & Delacretaz, N. 2009. Windows and vegetation: primary factors in Manhattan bird collisions. Northeastern Naturalist, 16: 455-470.

Parkins, K. L., Elbin, S. B., & Barnes, E. 2015. Light, glass, and bird—building collisions in an urban park. Northeastern Naturalist, 22: 84-94.