Urban Raptors

A parent Red-tailed Hawk flies from its nest over the New York City streets. Photo: François Portmann

New York City: the City that Never Sleeps, the Center of the Universe…and a major raptor hotspot? It comes as a shock to many that in our huge metropolis, birds of prey could find a place to even survive, let alone thrive. Learn about the birds of prey that surprisingly call New York City home.

The Big Apple has, in recent decades, become home to large resident and breeding populations of four diurnal raptor species: Red-tailed Hawk, Peregrine Falcon, American Kestrel, and Osprey. Three owl species—Great Horned, Barn, and Screech Owls—also nest in the City's largest parks. Bald Eagles have become year-round residents in recent years—and after several unsuccessful nesting attempts on Staten Island, fledged young there for the first time in 2017.

Fall through spring, Merlins, Sharp-shinned Hawks, and Cooper’s Hawks are frequently spotted (and a few pairs of Cooper’s Hawks actually breed here). Some winters, good numbers of owls including Barred, Northern Saw-whet, and even Snowy Owls are also observed. During migration, though the City cannot compete with the vast “kettles” sometimes recorded at mountainous hawk watch spots elsewhere in the fall, many migrating raptors are recorded at hawk watch spots in all boroughs

"}" data-trix-content-type="undefined" class="attachment attachment--content">

"}" data-trix-content-type="undefined" class="attachment attachment--content">Why Are They Here?

The presence of so many birds of prey in New York City in recent decades is in large part a testament to the success of country-wide environmental regulation and restoration efforts. The Bald Eagle, Peregrine Falcon, and Osprey were all brought back from steep population declines thanks to the federal government’s 1972 ban of DDT, a pesticide which caused egg-shell thinning and reproductive failure. The species have also benefited from passage of the federal Endangered Species Act in 1973, expansion of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, and dedicated conservation and restoration programs over many decades.

Our urban raptors’ arrival in New York City may also be due to other factors: It may reflect the recovering health and water quality of our city’s harbor ecosystem. These species may have simply learned to adapt to our urban landscape. It’s also possible that our birds have turned to urban and suburban landscape because more traditional, undeveloped habitats have become more scarce, or are already occupied.

It does seem that our ecosystem, both developed and undeveloped, supplies a good deal of sustenance that raptors need year-round—including the Rock Pigeons and Norway Rats of our most urban areas. This food source also represents one of the greatest dangers to the birds, in the form of poisoning. Learn how you can protect birds of prey from rodenticide poisoning.

It does seem that our ecosystem, both developed and undeveloped, supplies a good deal of sustenance that raptors need year-round—including the Rock Pigeons and Norway Rats of our most urban areas. This food source also represents one of the greatest dangers to the birds, in the form of poisoning. Learn how you can protect birds of prey from rodenticide poisoning.

Red-Tailed Hawks in NYC

Red-tailed Hawks have become a common breeding bird in New York City over the past 30 years. Photo: François Portmann

Perhaps the most celebrated of New York City’s raptors, this buteo with a rusty red tail breeds and lives year-round in all five boroughs. Learn more about the incredible comeback of Red-tailed Hawks in New York City in the past few decades and how you can help protect them.

Red-Tailed Hawks in NYC

Perhaps the most celebrated of New York City’s raptors, this buteo with a rusty red tail breeds and lives year-round in all five boroughs. Learn more about the incredible comeback of Red-tailed Hawks in New York City in the past few decades and how you can help protect them.

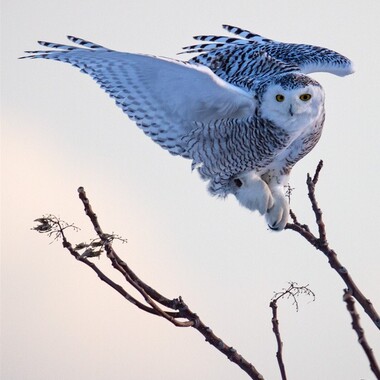

SNOWY OWLS AND AIRPORTS

Snowy Owls like this bird may easily wander to JFK Airport in search of prey. Photo: François Portmann

The iconic Snowy Owl is a true bird of the Great North. This powerful raptor breeds on the high Arctic tundra, in large part above the Arctic Circle. In the wintertime, the species ranges south across the wide expanse of Canada and the northern U.S. Most years, just a few Snowy Owls visit New York City and surrounding areas, observed only by the most determined winter birders.

SNOWY OWLS AND AIRPORTS

The iconic Snowy Owl is a true bird of the Great North. This powerful raptor breeds on the high Arctic tundra, in large part above the Arctic Circle. In the wintertime, the species ranges south across the wide expanse of Canada and the northern U.S. Most years, just a few Snowy Owls visit New York City and surrounding areas, observed only by the most determined winter birders.

RODENTICIDES

A Red-tailed Hawk captures a rat in Fort Tyron Park, Manhattan. Photo: Dave Bledsoe/CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

The methods we use to control rodents can have a devastating impact on our birds of prey. Rodenticides, also called rat poisons, are commonly used to control rodent populations.

RODENTICIDES

The methods we use to control rodents can have a devastating impact on our birds of prey. Rodenticides, also called rat poisons, are commonly used to control rodent populations.

A Red-tailed Hawk carries nesting material. Photo: François Portmann

Red-tailed Hawk

Red-tailed Hawk (Buteo jamaicensis)

Perhaps the most celebrated of New York City’s raptors, this Buteo with a rusty red tail breeds and lives year-round in all five boroughs. Learn more about the incredible rise of Red-tailed Hawks in New York City in the past few decades and how you can help protect them on our Red-tailed Hawks in NYC page.

A Red-tailed Hawk carries nesting material. Photo: François Portmann

Mating Red-tailed Hawks. Photo: François Portmann

A Red-tailed Hawk feeds its nestlings by the East Village’s Tompkins Square Park. Photo: François Portmann

A Peregrine Falcon in Flight. Photo: Paul Balfe/CC BY 2.0

Peregrine Falcon

Peregrine Falcon (Falco peregrinus)

The fastest flier in the world, clocked at over 200 miles per hour in a “stoop” (dive), the Peregrine Falcon has recovered from near extinction thanks to the banning of DDT and intensive captive breeding and release efforts. It remains listed as Endangered in New York State but has adapted well to the urban landscape, nesting on man-made structures (and often man-made nesting platforms) that mimic its natural cliff-face nesting spots.

New York City is actually thought to host the largest urban population of Peregrine Falcons in the world. The birds first nested on a city bridge in 1983, and now regularly nest on all bridges in the City. They stay year-round.

NYC Bird Alliance runs spring walks to see Peregrine Falcons in Upper Manhattan and the New Jersey Meadowlands. The species is frequently observed in Jamaica Bay, Central Park’s Reservoir, and other large open spaces in the City, as well as at established nest sites. If you see a Peregrine Falcon in trouble or become aware of a nest site being disturbed, give NYC Bird Alliance a call at 212-691-7483.

A Peregrine Falcon in Flight. Photo: Paul Balfe/CC BY 2.0

Peregrine Falcon nestlings on the Marine Parkway–Gil Hodges Memorial Bridge, in Queens, are banded by New York City Department of Environmental Protection Research Scientist Christopher Nadareski. Photo: New York City Department of Environmental Protection/CC BY 2.0

A Peregrine Falcon readies itself for takeoff. Photo: Lloyd Spitalnik

An American Kestrel in Flight. Photo: David Speiser

American Kestrel

American Kestrel (Falco sparverius)

Though it may “fly under the radar,” the American Kestrel is thought to be the City’s most abundant nesting raptor; at least some stay here year-round. Colloquially known as the “sparrow hawk,” this diminutive falcon has suffered sharp declines in much of its traditional rural habitat. It seems to be doing relatively well in New York City, however: it breeds in all five boroughs, often selecting building ledges as nest sites. (If you get to know its high, echoing “Killy-killy-killy” call, you will soon learn they are more common than you may think.)

American Kestrel fledglings are often discovered by concerned humans in the springtime, as they rest on window ledges, fire escapes, or even city sidewalks. They are best left alone or shifted to a safer nearby location to be fed by their parents, unless they are in immediate danger. Learn more about what to do if you find a baby bird.

An American Kestrel in Flight. Photo: David Speiser

American Kestrel fledglings in their New York City “nest.” Photo: François Portmann

A young male American Kestrel on his way. Photo: François Portmann

A Bald Eagle in Manhattan’s Riverside Park, January 2020. Photo: Bruce Yolton

Bald Eagle

Bald Eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus)

The Bald Eagle is another species that has rebounded spectacularly from near extinction, thanks to environmental regulation and dedicated conservation work. The population of our national symbol has grown steadily in New York State over the past decades, and for some time, the best bet to see Bald Eagles in our area was to head up the Hudson a bit to Croton Point, where the birds congregate on ice floes in the wintertime.

Eagles started to be regularly seen off of Inwood Hill Park in the 2010s, however, and several soon began living year-round in New York City. And in 2017, a major milestone occurred: after several unsuccessful nesting attempts in prior years, a pair on Staten Island fledged young for the first time. Eagles have continued to nest there, becoming a favorite of Staten Island locals. It may not be long before more Bald Eagles begin breeding across the City; they are often seen in other boroughs throughout the year as well: in Flushing Meadows Corona Park and Jamaica Bay Wildlife Refuge in Queens, and at several sites in northern Manhattan and the Bronx. Bald Eagles also now nest right outside the City, in both New Jersey and Long Island.

A Bald Eagle in Manhattan’s Riverside Park, January 2020. Photo: Bruce Yolton

Bald Eagles eat a wide variety of animals, as well as carrion, but their primary food prey is fish. Photo: François Portmann

A Bald Eagle is pursued by a Peregrine Falcon. Photo: François Portmann

Osprey nesting in Jamaica Bay Wildlife Refuge, Queens. Photo: Don Riepe

Osprey

Osprey (Pandion haliaetus)

The charismatic “fish hawk,” another success story following the banning of DDT, has experienced a worldwide recovery after a precipitous population decline in the 1950s and 60s. As the Osprey’s natural nesting sites of tree snags in coastal marshes, swamps, and fields became more and more scarce, the birds also learned to adopt man-made nesting structures. Their large, sticky nests are now a common site atop telephone poles and communications towers, and particularly on nesting platforms especially designed for them.

In recent years, over two dozen Osprey pairs have nested in the Jamaica Bay Wildlife Refuge, where Jamaica Bay Guardian and longtime NYC Bird Alliance supporter Don Riepe has been involved in the construction of many nesting platforms. Osprey are migratory, many wintering in Central and South America. In fact, an Osprey chick fitted with a GPS transmitter in Jamaica Bay in 2012, ”Coley,” was discovered to winter in Colombia. During nesting season, Osprey nest in many of the City’s wetlands, including Brooklyn’s Marine Park, Staten Island’s Great Kill Park and, and Queen’s Alley Pond Park.

Osprey nesting in Jamaica Bay Wildlife Refuge, Queens. Photo: Don Riepe

An Osprey in flight in Jamaica Bay Wildlife Refuge, Queens. Photo: François Portmann

An Osprey brings a fish to its nest in Jamaica Bay Wildlife Refuge, Queens. Photo: François Portmann

A juvenile Sharp-shinned Hawk (left) and juvenile Cooper's Hawk (right). Photo: Chuck Roberts/CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Sharp-shinned and Cooper's Hawks

Sharp-shinned Hawk (Accipiter striatus) and Cooper’s Hawk (Accipiter cooperii)

These two accipiter species are frequently seen in wooded areas of the city, and even in highly developed areas, during migration and over the winter. According to New York State Breeding Bird Atlas III, a few pairs of Cooper’s Hawks actually breed here, and no doubt benefit from the City’s large tracts of preserved land. Both these species, specialized in catching smaller birds, are known for hanging about winter feeding stations. They are also sometimes a challenge to distinguish, even for very experienced birders.

A juvenile Sharp-shinned Hawk (left) and juvenile Cooper's Hawk (right). Photo: Chuck Roberts/CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

An adult Sharp-shinned Hawk in flight; note its squared-off tail. Photo: Lloyd Spitalnik

An adult Cooper’s Hawk shows its rounded tail as it eyes a nearby prospect. Photo: Lucinda Mullins/Audubon Photography Awards

A fledgling Great Horned Owl takes flight in NYC. Photo: François Portmann

Great Horned Owl

Great Horned Owl (Bubo virginianus)

This large and fierce nocturnal predator has nested in recent years in a number of New York City’s larger parks, including the Bronx’s Pelham Bay Park and New York Botanical Garden, Jamaica Bay Wildlife Refuge in Queens, and the Staten Island Greenbelt. The species is also often seen on wintering territory in Central Park. When birding, always take care not to disturb owls; learn the ethics of considerate owl birding.

A fledgling Great Horned Owl takes flight in NYC. Photo: François Portmann

A Great Horned Owl in Central Park. Photo: Ellen Michaels

Young Great Horned Owls. Photo: Gene Putney/Audubon Photography Awards

Barn Owl. Photo: Sheribeari/CC_BY-ND_2.0

Barn Owl

Barn Owl (Tyto alba)

This adaptive, heart-faced owl lives across the entire globe. This predator of open spaces naturally builds its nest in tree cavities and caves, but has adapted to raise its young in many kinds of manmade structures. Nesting Barn Owls are frequently welcomed by humans, as rodents make up a large part of the birds’ diet. In New York City the species nest in a number of man-made nesting boxes in Jamaica Bay Wildlife Refuge.

Barn Owl. Photo: Sheribeari/CC BY-ND 2.0

Barn Owl nestlings in Jamaica Bay Wildlife Refuge, Queens. Photo: Don Riepe

A Barn Owl on the hunt. Photo: Stacy Howell/Audubon Photography Awards

Snowy Owl in flight. Photo: David Speiser

Snowy Owl

Snowy Owl (Bubo scandiacus)

This beautiful northern species, which visits NYC most winters, has become well-loved by a generation of children thanks to “Hedwig” the Snowy Owl, of the Harry Potter books. This popularity may have served it well in 2013, when many Snowy Owls descended on the City, resulting in a conflict with local airports. Learn more about NYC Bird Alliance’s efforts to protect Snowy Owls at Airports.

Snowy Owl in flight. Photo: David Speiser

A Snowy Owl strolls on a New York City-area beach. Photo: François Portmann

While Snowy Owls often sit directly on the ground, they are able to perch in trees—and display their feathered feet. Photo: François Portmann

The diminutive Northern Saw-whet Owl passes through New York City during migration and sometimes can be found roosting in low trees and shrubs over the winter. Photo: François Portmann

More Birds of Prey

More Birds of Prey

A number of other raptor species are regularly spotted in New York City throughout the year, including Northern Saw-whet Owl, Barred Owl, Northern Harrier, Merlin, Red-shouldered Hawk, Turkey Vulture, and others. To see what other raptors species occur here and when, see eBird bar charts for New York City, for the years 2000-2020.

Lucky birders may come across the round-headed Barred Owl roosting in our parks in the wintertime, though we rarely hear its "Who Cooks for You?" hoot here. Please keep your distance; owls need to rest! Photo: David Speiser

The owl-like Northern Harrier (here, a warmly colored young bird) may be found hunting low over grasslands and marshes; a few pairs may nest in the City. Photo: Keith Michael

The Merlin, or "pigeon hawk," smaller than the Peregrine Falcon (or "duck hawk") and larger than the American Kestrel (or "sparrow hawk"), passes through the City during migration and sometimes spends the winter. Photo: David Speiser