Get to Know the Harbor Herons!

Over the almost 40 years since wading birds were first discovered nesting on several islands west and north of Staten Island in the late 1970s, NYC Bird Alliance nesting surveyors have observed 10 species of egrets, herons, and night-herons nesting on 16 different islands around the New York/New Jersey harbor. Get to know the Harbor Herons below, from the most abundant species in the harbor to the least common, along with the cormorants and gulls that nest alongside them.

Click on each species below to see more photos and learn more.

Black-crowned Night-Heron

Black-crowned Night-Heron (Nycticorax nycticorax)

Overview: The Black-crowned Night-Heron is a striking gray, black, and white bird recognizable by its “hunched old man” posture. Though this global species migrates south in the wintertime from breeding territory across the northern reaches of North America and Asia, it stays in the New York City area year-round during milder years, and is also a resident along the southern coast and in much of Latin America and Caribbean. Outside breeding season, “Black-crowns” often roost together in large groups in trees hanging low over water. Like the Yellow-crowned Night-Heron, this species is most active at dusk and in the early morning, but is also often seen during the day—particularly during breeding season, when it requires a high calorie count to meet the challenges of breeding.

Where They Nest in NYC: Black-crowned Night-Herons are widespread nesters across our harbor, and in recent years have nested primarily in the large wader colonies on South Brother Island in the Bronx, Hoffman Island in the lower harbor, and several islands in Jamaica Bay, including Subway Island.

Nesting Details: Black-crowned Night-Herons build rather “disorderly,” flattish nests of fairly thick sticks, in a wide range of heights from near the ground to over 15 feet high, and lay 3-5 eggs. In mixed colonies their nests are often somewhat in the “middle,” below Great Egrets but above Snowy Egrets and Glossy Ibis. Black-crowned Night-heron chicks are particularly ferocious when approached, hissing loudly with mouths agape, like the tiny avian dinosaurs they are.

Numbers and Status: In New York City, it appears that the Black-crowned Night-Heron has declined in the past two decades from a high of 1,343 nesting pairs observed in 1993 to a survey low of 468 pairs in 2019. A decline in this species has been noted by other researchers along the Atlantic Coast, and its continent-wide population appears to have slightly decreased between 1966 and 2014, according to the North American Breeding Bird Survey.

NYC Bird Alliance Conservation Work: Due to its apparent decline in our survey, in early 2020 NYC Bird Alliance submitted our research data to the NY State Department of Environmental Conservation to support upgrading the conservation status of the Black-crowned Night-Heron in NY State to Threatened, which could afford it greater protections. We are waiting on a final decision, but this is an excellent example of why NYC Bird Alliance’s long-term monitoring data set is so valuable.

Where They Nest in NYC: Black-crowned Night-Herons are widespread nesters across our harbor, and in recent years have nested primarily in the large wader colonies on South Brother Island in the Bronx, Hoffman Island in the lower harbor, and several islands in Jamaica Bay, including Subway Island.

Nesting Details: Black-crowned Night-Herons build rather “disorderly,” flattish nests of fairly thick sticks, in a wide range of heights from near the ground to over 15 feet high, and lay 3-5 eggs. In mixed colonies their nests are often somewhat in the “middle,” below Great Egrets but above Snowy Egrets and Glossy Ibis. Black-crowned Night-heron chicks are particularly ferocious when approached, hissing loudly with mouths agape, like the tiny avian dinosaurs they are.

Numbers and Status: In New York City, it appears that the Black-crowned Night-Heron has declined in the past two decades from a high of 1,343 nesting pairs observed in 1993 to a survey low of 468 pairs in 2019. A decline in this species has been noted by other researchers along the Atlantic Coast, and its continent-wide population appears to have slightly decreased between 1966 and 2014, according to the North American Breeding Bird Survey.

NYC Bird Alliance Conservation Work: Due to its apparent decline in our survey, in early 2020 NYC Bird Alliance submitted our research data to the NY State Department of Environmental Conservation to support upgrading the conservation status of the Black-crowned Night-Heron in NY State to Threatened, which could afford it greater protections. We are waiting on a final decision, but this is an excellent example of why NYC Bird Alliance’s long-term monitoring data set is so valuable.

A Black-crowned Night-Heron gathers nesting material. Photo: Diana Robinson/CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Black-crowned Night-Heron nestlings on the Bronx’s South Brother Island. Photo: Mike Feller

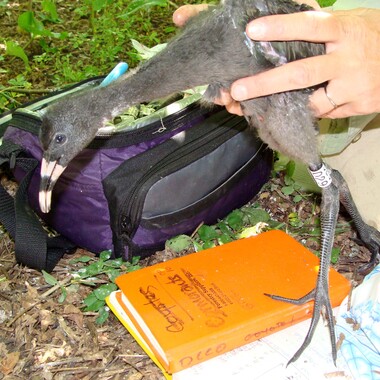

This Black-crowned Night-Heron had ingested a fish hook; it was found tangled in branches on Hoffman Island during our annual nesting survey. The hook was removed and the bird was released. Photo: NYC Bird Alliance

Great Egret

Great Egret (Ardea alba)

Overview: The Great Egret is the symbol of National Audubon for good reason: early Audubon founders were moved to fight for its survival over a century ago, when the species was under threat of extinction from the plume trade. (It is estimated that a shocking 95 percent of North American Great Egrets were killed for their plumes in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.) This striking all-white bird, which spreads its breeding plumes like a peacock when displaying for a mate, is identified by its large size as well as by its large, bright yellow bill and all-black legs and feet. Great Egrets are now considered a global species, our North American subspecies having been lumped with the former “Great White Egret” of the eastern hemisphere. American Great Egrets generally spend just the warmer months in most of the U.S. but are year-round residents throughout Central and South America.

Where They Nest in NYC: Most years, Great Egrets are the second most abundant nesting waders in the harbor, after Black-crowned Night-Heron—and like the night-heron, their largest numbers are found on the principal wader colonies of South Brother Island in the Bronx, Hoffman Island in the lower harbor, and several islands in Jamaica Bay, including Subway Island.

Nesting Details: Great Egrets are the largest waders in our colonial nesting colonies, and they “rule the roost”: their large, flat nests of sticks are generally the highest in a multispecies colony, and usually placed on top of foliage, open to the sun. Great Egrets typically lay 3-5 pale blue eggs. Nestling Great Egrets are distinctive in having bright green skin under their white pin feathers—a similar shade to the bright green lores (the facial skin between the eye and the bill) of the adult at the height of breeding season.

Numbers and Status: In New York City, the population of breeding Great Egrets appears to have increased slightly since the first Harbor Herons Nesting Survey in 1982. In recent years, its numbers have fluctuated between three and four hundred pairs. Continent-wide, the Great Egret population appears to have increased between 1966 and 2014, according to the North American Breeding Bird Survey.

NYC Bird Alliance Conservation Work: Since 2006, NYC Bird Alliance has placed leg bands on young Great Egrets and monitored resightings. Most recently, we have affixed satellite transmitters on several Great Egrets in New York Harbor, and tracked their movement.

Where They Nest in NYC: Most years, Great Egrets are the second most abundant nesting waders in the harbor, after Black-crowned Night-Heron—and like the night-heron, their largest numbers are found on the principal wader colonies of South Brother Island in the Bronx, Hoffman Island in the lower harbor, and several islands in Jamaica Bay, including Subway Island.

Nesting Details: Great Egrets are the largest waders in our colonial nesting colonies, and they “rule the roost”: their large, flat nests of sticks are generally the highest in a multispecies colony, and usually placed on top of foliage, open to the sun. Great Egrets typically lay 3-5 pale blue eggs. Nestling Great Egrets are distinctive in having bright green skin under their white pin feathers—a similar shade to the bright green lores (the facial skin between the eye and the bill) of the adult at the height of breeding season.

Numbers and Status: In New York City, the population of breeding Great Egrets appears to have increased slightly since the first Harbor Herons Nesting Survey in 1982. In recent years, its numbers have fluctuated between three and four hundred pairs. Continent-wide, the Great Egret population appears to have increased between 1966 and 2014, according to the North American Breeding Bird Survey.

NYC Bird Alliance Conservation Work: Since 2006, NYC Bird Alliance has placed leg bands on young Great Egrets and monitored resightings. Most recently, we have affixed satellite transmitters on several Great Egrets in New York Harbor, and tracked their movement.

A breeding pair of Great Egrets exchanges nesting material during courtship. As with most herons and egrets, the color of the Great Egret’s lores (the skin between the eye and bill) attains its most intense color at the height of the breeding season. Photo: Richard Fried

Great Egret adults and nestlings (with a few Snowy Egrets) on their nests, just a few feet from the ground, on Subway Island in Jamaica Bay. Photo: Don Riepe

Young Great Egrets (showing their green skin) on Subway Island in Jamaica Bay. Photo: Don Riepe

Snowy Egret

Snowy Egret (Egretta thula)

Overview: This delicate, all white heron was heavily hunted for its plumes in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, like its larger relative the Great Egret. Both species also recovered well after the hunting trade was stopped and all migratory birds were protected by 2018’s Migratory Bird Treaty Act. The Snowy Egret is recognized by its stylishly long head plumes, bright yellow lores, thin black bill, and black legs with bright yellow feet. Endemic to the Americas, Snowy Egrets stay in our area only during the breeding season, and are winter or year-round residents along the southern coast, in the Caribbean, and throughout Central and South America.

Where They Nest in NYC: Snowy Egrets currently nest in good numbers on South Brother Island in the Bronx, Hoffman Island in the lower harbor, and several islands in Jamaica Bay; their population has grown quickly in recent years on the restored marsh islands of Elders Point East and West.

Nesting Details: Snowy Egret nests are recognizable by how delicate they are: typically a neat, circular arrangement of very fine sticks, with similarly delicate, small, light blue eggs. Clutch size is typically larger than similar species, often consisting of five or six eggs. “Snowy” nests are often found rather low in thick foliage, quite frequently directly underneath the large nests of the Great Egret. Snowy Egret chicks have pinkish bills and very fluffy tufts of down atop their heads.

Numbers and Status: In New York City, the population of breeding Snowy Egrets has remained fairly stable since the first Harbor Herons Nesting Survey in 1982. In recent years, approximately two to three hundred pairs have nested in the harbor. Continent-wide, the Snowy Egret population remained stable between 1966 and 2014, according to the North American Breeding Bird Survey.

NYC Bird Alliance Conservation Work: Since 2006, NYC Bird Alliance has placed leg bands on young Snowy Egrets and monitored resightings. Snowy Egrets are among the species that in recent years have abandoned formerly productive nesting islands, like Goose Island in the Bronx or Mill Rock in the East River, possibly due to human disturbance. We post signage on nesting islands to discourage visitation during the breeding season and advocate for the presence of Parks staff to further protect the colonies.

A Snowy Egret in breeding plumage, showing its curved back plumes, or “aigrettes.” Photo: Don Miller/CC BY 2.0

A Snowy Egret nestling on Hoffman Island. Photo: Debra Kriensky

A Snowy Egret nest, constructed of fine twigs and reeds, on South Brother Island in the Bronx. Photo: Debra Kriensky

Glossy Ibis

Glossy Ibis (Plegadis falcinellus)

Overview: The Glossy Ibis, a long-billed, small wader that may in part be the inspiration for “Gonzo” on the Muppet Show, is often overlooked; it usually appears all dark, but in the right light, its plumage reveals sparkles of intense, iridescent color: bronze, violet, and green. A worldwide species, the Glossy Ibis has a relatively limited range in the Americas; it visits the Northeast Coast only during the breeding season, and is a resident or wintering species along the southeastern coast of the U.S., and either a resident or wintering species in the Caribbean and Central America.

Where They Nest in NYC: In recent years, Glossy Ibis have only nested in good numbers on a few islands in the southern part of the harbor—on Hoffman Island and on Subway Island in Jamaica Bay.

Nesting Details: If we think of a wader colony as a house, the Glossy Ibis definitely lives in the basement: it builds its dense, stacked nest of matted reeds, grass, and soil on the ground or on very low branches. The typical 3-4 eggs of the “Glossy” are a darker blue than those of its companion wader species. Ibis chicks are a distinctive, fuzzy black, and have a fairly short, pale bill with a dark ring. They quickly flee their nest on foot when approached, hiding in the underbrush.

Numbers and Status: In New York City, the breeding Glossy Ibis population tends to fluctuate a great deal from year to year, but has remained fairly stable over the time of our nesting survey, usually falling between one and three hundred pairs. Continent-wide, the Glossy Ibis population increased almost eight-fold between 1966 and 2015, according to the North American Breeding Bird Survey. This substantial rise in population reflects the fact that the Glossy Ibis is thought to have first colonized North America only in the 1800s, and has expanded its range throughout the 20th century.

NYC Bird Alliance Conservation Work: Since 2006, NYC Bird Alliance has periodically placed leg bands on young Glossy Ibis and monitored resightings. NYC Bird Alliance is also participating in a global study of Glossy Ibis genetics, collecting feather samples from NYC-born Glossy Ibis. Dr. Susan Elbin and Emilo Tobón recently authored an article on Glossy Ibis nesting in the City for the inaugural issue of the research publication Stork, Ibis, and Spoonbill Conservation.

When seen in the right light, Glossy Ibis are indeed “glossy” with iridescent color. Photo: Matthew Paulson/CC BY-NC 2.0

Glossy Ibis perched in trees on the Subway Island nesting colony in Jamaica Bay. Photo: Don Riepe

A Glossy Ibis chick, just banded, on Hoffman Island in the lower New York Harbor. Photo: NYC Bird Alliance

Yellow-crowned

Yellow-crowned Night-Heron (Nyctanassa violacea)

Overview: The Yellow-crowned Night-Heron, while superficially similar to its black-crowned relative, is a svelter bird with a different style: the species’ Latin genus names help describe the difference: Nycticorax, or “ night crow” for the rather hunched Black-crowned Night-Heron; Nyctanassa, or “night lady” for the longer necked, more graceful Yellow-crowned Night-Heron. The latter is also distinguished by its light yellow crown—as well as by its striking black-and-white face pattern, uniformly medium-dark body, and longer legs in flight. Here in New York City, we are the northern edge of the Yellow-crowned Night-Heron’s range; it summers in the eastern United States, and is a resident in southern Florida, the Caribbean, and the coasts of Latin America.

Where They Nest in NYC: Though small numbers of Yellow-crowned Night-Herons nest on a few islands in the harbor, this wader species is unusual in that the majority of its population breeds on the mainland, usually near the tidal creeks and mudflats where it finds the crabs and other crustaceans that form the vast majority its diet. The biggest colony of Yellow-crowned Night-Herons, at about 60 nests in recent years, is in the courtyards of the Redfern Houses community in Far Rockaway Queens. The birds nest high in Honey Locust and Willow Oak trees, often just feet from the windows of residents. The City’s population may be growing, as smaller colonies have been appearing in recent years in the neighborhoods of Brooklyn, Queens, the Bronx, Staten Island, and even in the borough of Manhattan (one or two pairs have nested on Governors Island for several years).

Nesting Details: The Yellow-crowned Night-Heron builds a rather sloppy nest of fairly thick sticks, similar to that of its black-crowned relative—but often includes a little green foliage among the sticks. The clutch size is typically 3-4 eggs. Like other herons, Yellow-crowned Night-Herons lie flat when sitting on their nests—and as a result are often nearly invisible when viewed from below.

Numbers and Status: Because NYC Bird Alliance has not conducted a methodical study of mainland colonies in New York City, we cannot be certain of any change in the species population over time. Anecdotally, however, its population does seem to be increasing, fueled by a growth in mainland colonies. Its continent-wide population appears to have remained stable or declined slightly between 1966 and 2014, according to the North American Breeding Bird Survey.

NYC Bird Alliance Conservation Work: NYC Bird Alliance surveyors maintain a friendly relationship with the Redfern Houses staff and residents, who observe their community’s nesting birds on a daily basis and have been helpful in providing information about the colony (such as the presence of predators). In 2018, the staff also informed surveyors of a second Yellow-crowned Night-Heron colony on the Rockaway Peninsula.

Yellow-crowned Night-Herons specialize in feeding on crabs and other crustaceans, which they find in the City’s tidal creeks and marshes. Photo: Lloyd Spitalnik

Lucky birders sometimes come across a Yellow-crowned Night-Heron displaying its breeding plumes. All of our herons and egrets are able to raise certain feather tracts, much like Peacocks do. Photo: François Portmann

One or two pairs of Yellow-crowned Night-Herons have been observed nesting on Governors Island since 2015. Photo: Bruce Yolton

Little Blue Heron

Little Blue Heron (Egretta caerulea)

Overview: The adult of this small, elegant heron is all dark; in the sunlight, its bronze-purple neck and head is distinct from its slate-blue body. But don’t be fooled by the immature bird, which is mostly white (usually with small smudges of darker feathers on the back or wings), and can be confused with the Snowy Egret. At all ages, it is a slightly sturdier bird than the Snowy—and the young bird is distinguished by its thicker, blueish bill with dark tip, and by its greenish legs and feet. Endemic to the Americas, the Little Blue Heron is at the northern end of its range in New York City. The species migrates south in the winter and is a resident along our southeastern coast, and either a resident or wintering species in the Caribbean and Latin America.

Where They Nest in NYC: A few pairs of Little Blue Herons nest every year in the southern part of the Harbor—on Hoffman Island on one or more islands in Jamaica Bay.

Nesting Details: Because so few Little Blue Herons nest in the harbor, our surveyors rarely get a chance to observe their nests—but Little Blue Herons are known to build sheltered nests fairly low in shrubs and trees, similar to the Snowy Egret, of fairly fine sticks and grasses. Their clutch size is typically 3-4 eggs.

Numbers and Status: Little Blue Herons have maintained a continuous small population in the harbor over the decades of our nesting survey; in recent years, usually 5-10 pairs nest here. The Little Blue Heron population declined 55 percent between 1966 and 2014, according to the North American Breeding Bird Survey, most likely due to habitat loss and declines in water quality.

An adult Little Blue Heron with a small fish, its primary prey. Photo: Laura Meyers

A banded fledgling Snowy Egret (left) and Little Blue Heron (right). Immature Little Blue Herons are mostly white, and can be confused with Snowy Egrets—but note the stouter bill, grayish lores (the skin between the eye and the bill), and dark wing tips of the Little Blue Heron (banded July 14, 2015). Photo: NYC Bird Alliance

Little Blue Heron “1Z,” banded on Elders Point East Marsh Island on July 14, 2015, was photographed on August 30, 2015, by local birding expert Doug Gochfeld. (Note the smudges of dark blue on the bird’s primary feathers.) Photo: Doug Gochfeld

Tricolored Heron

Tricolored Heron (Egretta tricolor)

Overview: The beautiful, delicate Tricolored Heron (formerly known as the “Louisiana Heron”) is a rare treat when spotted in New York City. It is ID’d by its dark-blue and bronze upper parts and distinct white belly, underwing coverts, and throat stripe, as well as its long, dagger-like bill. The color of the Tricolored Heron’s lores and bill varies from bright yellow outside of nesting season to a neon blue while breeding. Endemic to the Americas, the Tricolored Heron is at the northern end of its limited range in New York City. The species migrates south in the winter and is a resident along our southeastern coast, and either a resident or wintering species in the Caribbean, Central America, and the northern coast of South America.

Where They Nest in NYC: Tricolored Herons nest most years in Jamaica Bay.

Nesting Details: In Jamaica Bay, Tricolored Herons nest on low marsh islands in proximity to Great and Snowy Egrets and Little Blue Herons. They build a bulky nest of sticks and normally lay a clutch of 3-5 eggs.

Numbers and Status: Tricolored Herons have maintained a continuous but very small population in the harbor over the decades of our nesting survey; in most years, one or two pairs nest here. The species’ U.S. population has remained stable between 1966 and 2014, according to the North American Breeding Bird Survey.

The spectacular Tricolored Heron can raise its head plumes into a crown. Note the blue lores (the skin between the eye and the bill), which are present only during the height of breeding season; the rest of the year, the lores are bright yellow. Photo: Mark Schwall

The Tricolored Heron aggressively chases small fish, foraging with quick, darting movements and sometimes raising its wings. Photo: Heather Paul/CC BY-ND 2.0

Immature Tricolored Herons have patchy rust-colored plumage, where the adult is slate blue and purple. Photo: Kenneth Cole Schneider/CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Green Heron

Green Heron (Butorides virescens)

Overview: The diminutive, secretive Green Heron is a striking bird of green and chestnut with a yellow eye and patterned face and throat. At the height of breeding season, the adult’s legs turn from yellow to bright orange. Unlike most of the Harbor Herons, this species prefers freshwater habitats. Though it can nest in small, loose colonies, it often nests alone. It is most often seen foraging or perched at the edge of wooded ponds or streams, often with its neck so well tucked in that it appears nonexistent. This species of the Americas breeds in the eastern U.S. and on the West Coast, and is a resident along our southern coasts, and either a resident or wintering species in the Caribbean and northern Latin America.

Where They Nest in NYC: Though Green Herons have occasionally been observed nesting on the Harbor Heron Islands, for the most part they nest on the mainland near fresh water. The species nests in small numbers in larger wooded parks with fresh water in the City: A pair nested by the Central Park Lake in the past; in recent years a pair has nested regularly in Brooklyn’s Prospect Park. Green Herons also nest in Alley Pond Park, and at several sites on Staten Island including Clove Lakes Park.

Nesting Details: Green Herons build a well-concealed nest of sticks in a tree or shrub, often over a pond or stream. They lay a clutch of 3-5 bluish green eggs; young are a downy gray.

Numbers and Status: Green Herons are not regularly counted by our nesting survey as they are a mainland species, but small numbers are reported most years from mainland sites. The Green Heron population declined 68 percent between 1966 and 2014 in the U.S., according to the North American Breeding Bird Survey; loss of wetland habitat is thought to be a primary cause of the decline.

An adult Green Heron in Brooklyn’s Prospect Park, where the species nests most years. Photo: Ryan Mandelbaum/CC BY 2.0

Hunting Green Herons may stay stock still for minutes on end before nabbing its prey (usually a fish, amphibian, or insect) with a sharp lunge. Photo: David Speiser

A nestling Green Heron peeks out from its nest in Brooklyn’s Prospect Park. Photo: Ryan Mandelbaum/CC BY 2.0

Great Blue Heron

Great Blue Heron (Ardea herodias)

Overview: This largest of our herons is unmistakable due to its great size; light blue, tan, and chestnut body; black-and-white cap; and powerful yellow bill. Like its much smaller relative the Green Heron, this species prefers freshwater habitats for breeding; typically nesting in large colonies in wooded swamps. Though only a few pairs are known to nest in New York City each year, the species is a fairly common sight on ponds and lakes in the City. Though very similar in appearance to the Gray Heron of the old world, the Great Blue Heron is endemic to the Americas. It is a resident in our area and across most of the U.S., and a resident or wintering species in Central American, the Caribbean, and northern South America.

Where They Nest in NYC: A pair of Great Blue Herons has nested in Staten Island’s Clove Lakes Park since 2013, and the species also appears to nest in or near Pelham Bay Park. Other young birds seen in the City may be recent fledges from nearby nesting pairs in New Jersey or on Long Island.

Nesting Details: Great Blue Herons build a platform of sticks and twigs lined with sotter materials, often in trees, and sometimes in very large colonies placed high in large trees of swamps or flooded woods.

Numbers and Status: Great Blue Herons nest regularly in very low numbers in the City. Its U.S. population has remained stable or increased between 1966 and 2014, according to the North American Breeding Bird Survey, though population declines have occurred in some areas.

An adult Great Blue Heron flies over the Jamaica Bay. Photo: François Portmann

A Great Blue Heron raises its plumes in a breeding display. Photo: David Speiser

Young Great Blue Herons (note their dark foreheads, vs. the white cap of the adult) beg to be fed by a parent in Clove Lake Park on Staten Island, where one pair has nested since 2013. Note the adult’s thick neck; it is most likely carrying food in its crop, to be regurgitated for its fledglings. Photo: Dave Ostapiuk

Cattle Egret

Cattle Egret (Bubulcus ibis)

Overview: This adventurer of an egret is not native to the Americas, but is believed to have arrived here on its own steam in recent times. Native to the southern land masses of the old world, a small breeding population of the species somehow arrived in northern South America on its own in 1877, perhaps perched upon floating debris from Africa. The species rapidly spread, first nesting in the U.S. in 1953 and rapidly spreading across the continent. This small, chunky white egret is most striking in breeding season, when it grows orange head, breast, and back plumes, and its yellow legs and bill turn bright orange.

Where They Nest in NYC: One breeding-plumaged Cattle Egret was observed during our 2019 survey of Hoffman Island. This is the first time this species has been observed during the nesting survey since 2010; see “Numbers and Status” below to learn more.

Nesting Details: The Cattle Egret is a versatile species that establishes colonies in trees or shrubs in a variety of habitats, including dry upland woods, swamps, marshes, and wooded islands. The Cattle Egret nest is similar in size to that of the Snowy Egret, but tends to be a looser, coarser structure.

Numbers and Status: Before the Cattle Egret observed on Hoffman Island during our 2019 survey, the last time breeding was confirmed was 2010, when one pair was estimated on Canarsie Pol. The harbor-wide breeding Cattle Egret population declined to zero in 2011 from a high of 266 nests on two islands (Prall’s and Shooters islands) in 1985. A possible cause of this decline was closure of local landfills that were a foraging source. The U.S. Cattle Egret population declined 50 percent between 1966 and 2015 in the U.S., according to the North American Breeding Bird Survey.

A breeding-plumaged Cattle Egret, showing intense color in the bill and face. Photo: Subash BGK/CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

In April 2017 a breeding-plumaged Cattle Egret appeared in the courtyard of a building complex in Manhattan’s Chelsea; the bird stayed several weeks, appearing to feed on lawn insects and roosting in courtyard trees at night. Photo: François Portmann

Can you find the Cattle Egret? This photo shows the difference in size and proportion between four Great Egrets and one Cattle Egret. Photo: Radovan Václav/CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

.jpg)

Double-crested Cormorant

.jpg)

Double-crested Cormorant (Phalacrocorax auritus)

Overview: In recent decades, the Double-crested Cormorant has become a common sight at any large body of water in New York City. The species breeds and winters across the North American continent, from Alaska to southern Mexico; after nesting on islands in our harbor, many cormorants migrate south, though a good number stay year-round. Like other members of its worldwide family, this species is well adapted to its aquatic lifestyle, and to catching fish, its primary prey. Cormorants lack the productive oil glands that keep the feathers of most waterbirds water-proofed. As a result, their feathers get wet, making them the birds less buoyant—and very quick and agile swimmers underwater. The drawback of this adaptation is that cormorants must dry their wings, which they do by holding them open in the sun.

Where They Nest in NYC: Double-crested Cormorants nest on several islands around the harbor: they share nesting colonies with long-legged waders on South Brother and Mill Rock Islands in the East River, Hoffman Island in the lower harbor, and Elders Point West Marsh Island in Jamaica Bay. They also have a large nesting colony on Swinburne Island, next to Hoffman Island, and a small colony on U Thant Island, in the East River. Cormorants also nest on aids to navigation in Newark Bay and around Staten Island.

Nesting Details: Cormorant nests are rather messy affairs built from large sticks, in New York City often mixed with man-made materials such as netting, rope, and trash. Cormorants nest in large colonies, in trees when available, though their guano often kills the trees in which they nest. In Jamaica Bay and on Swinburne Island, most birds nest directly on the ground. Double-crested Cormorants lay 1-7 eggs.

Numbers and Status: Double-crested Cormorant populations have recovered from declines in the 19th and 20th centuries due to overhunting and pesticides such as DDT. The New York City population of Double-crested Cormorants has been steadily increasing in the harbor since 2005; in recent years, around 2,400 pairs of cormorants have bred here. Across the U.S., this species’ population increased steadily between 1966 and 2015, according to the North American Breeding Bird Survey. Because Double-crested Cormorants are perceived to compete with the fishing industry, they are often subject to management by both federal and state agencies. Read about New York State policy.

.jpg)

An adult Double-crested Cormorant on its nest (which is often on the ground, like this one). Note the “crests” of this bird’s breeding plumage, as well as the surprising color of its eyes and mouth. Photo: NYC Bird Alliance

Young Double-crested Cormorants on their nest on Swinburne Island, in the lower harbor just south of the Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge. These fledglings have just been banded by NYC Bird Alliance; an orange band is just visible on the leg of the right-most bird. Photo: Don Riepe

Recently hatched Double-crested Cormorant chicks on Jamaica Bay’s Elders Point East Marsh Island. Photo: Jeffrey Kolodzinski

Herring Gull

Herring Gull (Larus argentatus)

Overview: This large, common gull species is unmistakable, at least as an adult: its slate gray back and white head, black wing tips, big yellow bill, and pink legs set it apart from other species. It belongs to what is called a “ring distribution” of closely related gulls around the northern hemisphere—and depending on which expert you consult, “our” Herring Gull is considered a worldwide species or one that is endemic to the Americas. (For example, while European authorities consider the European and American Herring Gulls separate species, both the American Ornithologists’ Union and Cornell Lab of Ornithology consider the two to be subspecies of the same overarching species.) Herring Gulls are year-round residents in New York City.

Where They Nest in NYC: Herring Gulls nest on most the islands occupied by nesting waders and cormorants. The species’ biggest colonies are on Hoffman and Swinburne Islands in the lower harbor, and on several islands in Jamaica Bay including Subway, Little Egg, and Elders Point West Marsh Islands. Herring Gulls also nest on rooftops, including that of Rikers Island and the Jacob K. Javits Convention Center green roof. (Learn more about the [a href = “our work/protecting urban habitat/green roofs and infrastructure”]Javits Center green roof[/a].

Nesting Details: Herring Gulls create shallow, circular scrapes in the soil, usually lined with a small amount of grasses and stems. They usually lay three spotted brown eggs, slightly smaller than those of the Great Black-backed Gull; measurements must often be taken to be certain to which species a nest belongs.

Numbers and Status: Our American Herring Gull, like many waterbird species, suffered from overhunting in the 19th century, as well as from harvesting of its eggs for food. The species recovered substantially in the first half of the twentieth century, and actually expanded its breeding range southwards, possibly aided by the availability of human refuse in landfills. Before 1910, its southern-most nesting area was Maine; it now nests and is a year-round resident as far south as the Carolinas. Despite this recovery, however, the U.S. Herring Gull population declined 83 percent between 1966 and 2015 in the U.S., according to the North American Breeding Bird Survey. Possible causes of the decline include scarcity of food due to overharvesting of fish stocks by human industry.

NYC Bird Alliance Conservation Work: Since 2010, NYC has placed leg bands on young Herring Gulls and monitored resightings. Banded gulls have been seen in seven different states and as far south as Louisiana.

A nesting Herring Gull in Jamaica Bay. Herring gulls nest on the ground. Photo: NYC Bird Alliance

Herring Gull adult and immature on Hoffman Island. Photo: Debra Kriensky

A just-banded fledgling Herring Gull on Hoffman Island. Each bird gets a metal “federal band” (with a number assigned by the U.S. Geological Survey Bird Banding Lab) and a plastic “field readable” band (the orange band on this young Herring Gull, which is larger and easier to spot by observers in the field). Photo: Debra Kriensky

Great Black-backed Gull

Great Black-backed Gull (Larus marinus)

Overview: The largest gull on Earth, the Great Black-backed Gull has a bigger wingspan than an Osprey (65 vs. 63 inches). It’s so large that when viewing it from a distance, birders may double check a soaring Great Black-backed Gull to make sure they’re not seeing a Bald Eagle. This white-headed gull with a black back and upper wings, yellow bill, and pink legs lives along the coast of both sides of the northern Atlantic, and is a year-round resident in New York City. The species is an omnivorous predator—birders are sometimes shocked to discover that in addition to marine invertebrates, the Great Black-backed Gull’s prey includes both young and adult birds, such as smaller gulls, terns, and ducks.

Where They Nest in NYC: Great Black-backed Gulls nest alongside Herring Gulls on most of the long-legged wader colonies in the harbor. This species’ biggest colonies are on Hoffman and Swinburne Islands in the lower harbor, and on several islands in Jamaica Bay including Subway, Little Egg, and Elders Point West Marsh Islands. A number of pairs also nest on Mill Rock Island and U Thant Island, both in the East River.

Nesting Details: Great Black-backed Gulls create shallow, circular scrapes in the soil, usually lined with a small amount of grasses and stems. Usually, this largest of gulls takes the higher ground in mixed colonies with Herring Gulls. They also usually breed earlier than Herring Gulls, and as a result, most chicks that Harbor Herons nesting surveyors see in mid-May are of this species, rather than Herring Gull.

Numbers and Status: In the 19th century, egg collection and hunting for the feather trade nearly led to the extirpation of Great Black backed Gull in North America. Like the Herring Gull, this species recovered substantially in the first half of the twentieth century, and actually expanded its breeding range southwards, often outcompeting Herring and Laughing Gulls for breeding sites. And, like the Herring Gull, the species declined in the U.S. in the last half century, according to the North American Breeding Bird Survey; between 1966 and 2017, its numbers have fallen by 74 percent. Great Black-backed Gull colonies are managed by wildlife agencies to allow smaller bird species to nest, such as terns and Atlantic Puffins.

Great Black-backed and Herring Gulls on Hoffman Island. Where the two species share a nesting island, Great Black-backed Gulls tend to claim the higher (and presumably less flood-prone) ground for nesting. Photo: Debra Kriensky

When presented with danger, young gull chicks like these will leave the nest on foot, find a hiding place (in foliage or among rocks), and sit still. Photo: Debra Kriensky

While the black wings and back of the Great Black-backed Gull are very distinct when viewed from above, from below, it can be harder to differentiate this species from the Herring Gull. Careful observation reveals the darkness of the upper wing through the primary and secondary feathers, however. Photo: Stefan Berndtsson/CC BY 2.0

More Island Nesters

More Island-Nesting Colonial Waterbirds

Several other waterbird species nest on upland and saltmarsh islands in New York City.

Common Terns have nested at several known locations in recent years: Governors Island, Little Egg Marsh Island and Joco Marsh in Jamaica Bay, and beach sites on the Rockaway Peninsula. Read about them on our page about beach-nesting birds.

American Oystercatchers breed on a number of islands around the harbor, with the largest population in Jamaica Bay. This species also nests on the beaches of the Rockaways, on Staten Island’s South Shore, and in the Bronx’s Pelham Bay Park. Read about them on our page about beach-nesting birds.

Laughing Gulls and Forster’s Terns nest in Joco Marsh, an extensive, tidally flooded saltmarsh adjacent to the runways of John F. Kennedy International Airport. This colony is not known to have included breeding waders or cormorants, and has not traditionally been surveyed as part of NYC Bird Alliance’s Harbor Herons nesting survey. NYC Bird Alliance collaborates periodically in a survey of Joco Marsh by a group of agencies and organizations including National Park Service, NYC Parks, the American Littoral Society, the Port Authority of New York & New Jersey, and USDA/APHIS.

Common Terns and American Oystercatchers nest both on NYC beaches and several of the Harbor Heron islands, particularly in Jamaica Bay. Photo: Don Riepe

Forster's Terns, known by their long white tail feathers and silvery upper primaries, nest in Joco Marsh in Jamaica Bay, as well as in Staten Island's Fresh Kills Park. Photo: Ryan F. Mandelbaum

Laughing Gulls nest in good numbers in Jamaica Bay's Joco Marsh, but are found throughout the City in the summertime. Photo: Lawrence Pugliares

Learn More and Find Out Where to See the Harbor Herons and Other Island-Nesting Waterbirds

To learn more about when and where you can see waders and other waterbird species in the City, see eBird bar charts for New York City, for the years 2000-2020.

The Harbor Heron Islands are closed to the public in order to protect the nesting birds, which are easily disturbed. But fortunately, there are many places to see foraging wading birds and other island-nesting waterbirds in New York City.

Excellent spots include:

· Jamaica Bay and Alley Pond Park in Queens

· Pelham Bay Park in the Bronx

· Marine Park Preserve and Calvert Vaux Parks in Brooklyn

· Randall’s Island in the borough of Manhattan

· and many sites on Staten Island

Sources for “Get to Know the Birds”

New York Breeding Bird Atlas III eBird data courtesy of Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA.

Sauer, J. R., D. K. Niven, J. E. Hines, D. J. Ziolkowski, Jr, K. L. Pardieck, J. E. Fallon, and W. A. Link. 2017. The North American Breeding Bird Survey, Results and Analysis 1966 - 2015. Version 2.07.2017 USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, Laurel, MD